When people think of the Pacific, often what comes to mind is a picturesque paradise of coconut trees, pristine seas and happy smiling natives. This idea has been around since the first Europeans discovered the Polynesian isles (and the people already living on them). And, much like the stereotypes that plague any other minority group, it’s still clinging to us.

The thing about Pacific Islanders is, we consist of such a small population of people that we often get put into other bigger groups. Most of the time it’s the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) umbrella we’re put under, which is fairly accurate, even if Pacific Islanders are the overwhelming minority. As a result, when it comes to representation in mainstream media, Pacific Islanders don’t get much of it. There’s plenty of Pacific island literature and art, but very little of it ever sees mainstream success. Largely because the avenues to mainstream success have been closed off to them.

Nowadays however, there are more nuanced Pacific Island representations making their way into popular media, as well as the indie and local scene. Much of this can be attributed to a generation of Pacific Islanders growing up with a wealth of art to inspire them. It can also be attributed to changing attitudes towards indigenous people and the realisation that inclusivity is an effective way to draw audiences.

So we’re going to take a look at the way Western culture has depicted Pacific Islanders in media and how Pacific Islanders depicted themselves in their own artwork.

Table of Contents

First Impressions

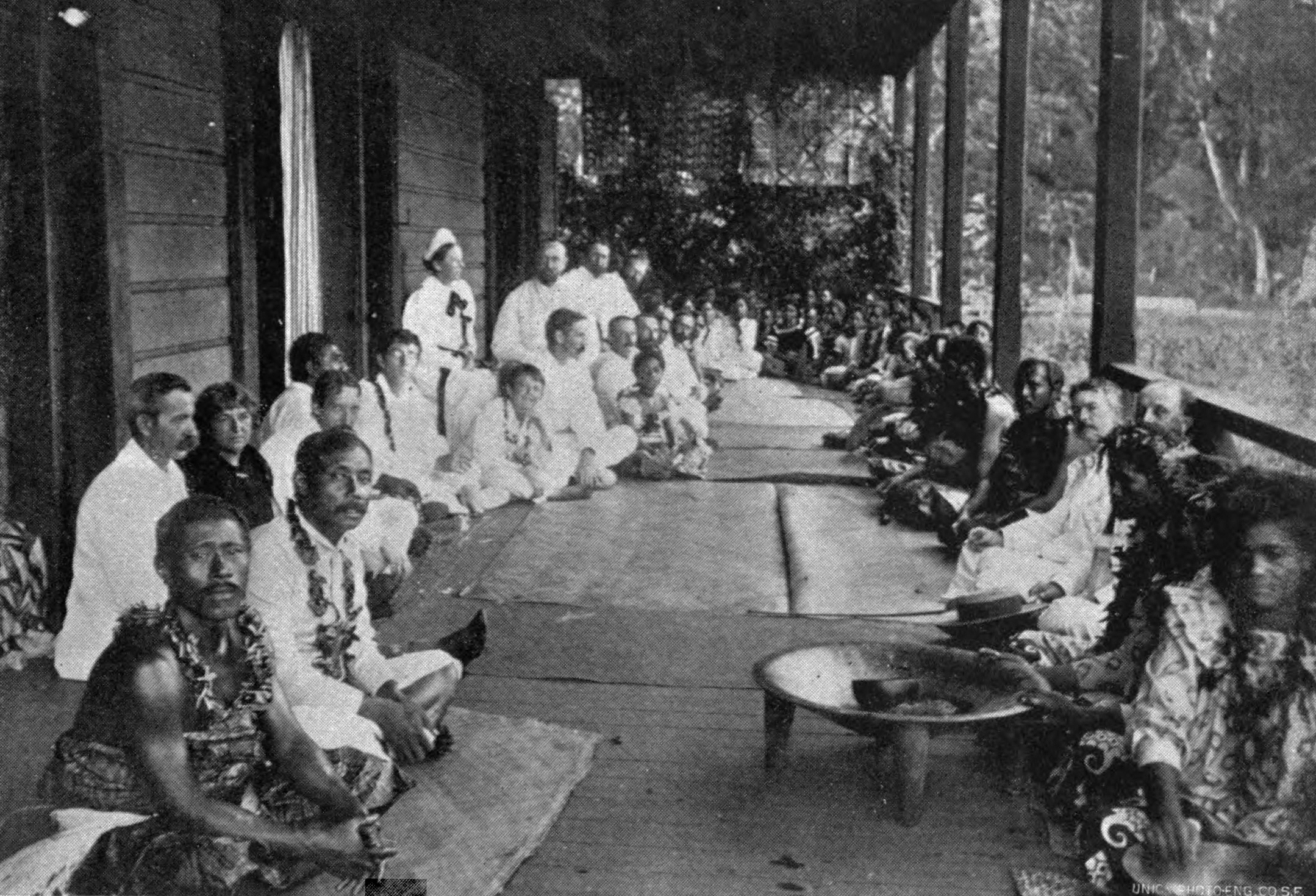

The first Europeans had a lot to say about Pacific Islanders when they first encountered them. The prevailing idea was that Pacific Islanders were inferior and that, one way or another, it was their prerogative to show Pacific Island peoples the error of their ways.

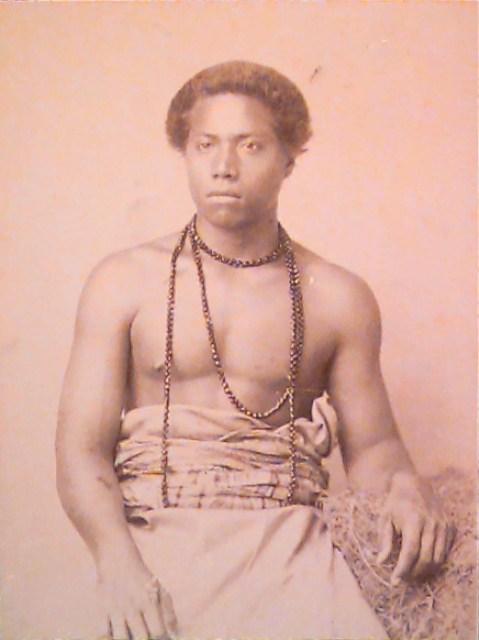

In the same way that Europeans had some very… interesting opinions about how dark skinned people looked, they held the same strange language for Polynesians. At first it’s what you expect from a European in the 1700s, but their views began to shift in strange ways, for one, we were labelled a ‘noble savage’ kind of people, akin to ‘Eve, before her fall’ (Tcherkézoff, 2008).

This attractiveness led to people thinking Polynesia was a kind of Eden, inhabited by strong (albeit passive) peoples. Many Europeans had pointed opinions about the practices that Pacific Islanders engaged in, but that didn’t stop them from settling on the islands and establishing commercial roots.

Soon enough, stories would reach their respective countries about these idyllic islands, feeding into the idea that the Pacific was a carefree land of carefree peoples. It of course didn’t start out this way, but as the Europeans settled, their image of Polynesians began to change.

And so the first few depictions of Polynesians changed from untrustworthy, bloodthirsty thieves to kindly, simple people who smiled all the time and never indulged in silly things like ambition or anger. The thievery idea remained.

Sexuality was also portrayed. They followed the typical depiction of brown people in stories: hypersexual men and women, though the women always ended up with someone white and the brown men were very upset about it, usually when they weren’t seducing European women.

Regardless, the depiction lasted into the late 20th Century when Hollywood began to amplify it. Movies like Return to Paradise and Hurricane depict Polynesian characters falling in love with American characters. It didn’t help as well that a lot of Hollywood studios didn’t actually hire Pacific Islanders for some of their roles and simply added a few tanned folks to cover up the slack. It leads to a very skewed view of what life was like and in some cases remains to be for modern islanders. (Britannica, 2024)

Representation: A Matter of Perspective

Representation seems like a relatively new idea, but the concept has been around for a long time. But it wasn’t as widely available, nor widely pervasive, as when movies and thus the entertainment mega-industry exploded into the scene. African Americans, as well as many other groups including Latin, Asian and Native communities had been relegated to degrading portrayals. Many of them were different varieties of patronising, humiliating or blatantly revisions of history. Much of these stereotypes existed in literature, but movies soon became extremely popular, and with them, the cliches associated. (Schacht, 2019; Allen, 2023; Nittle, 2020; The Will to Change, hooks, 2003)

Being an industry dominated by a certain group of people, anyone outside the perceived norm were denied their voice. As time went on, many members of these groups began to tell their own stories. And in time, their stories went from being outliers, to major cultural touchstones.

This is the first reason why representation, as in good, authentic representation is important. Stereotypes, whether they be negative or positive, present a group of people in an inherently limited light. A common type casting of Polynesian people is that of the big, strong character. While this depiction can be seen as positive, depictions like this often boil us down to that ideal, and very little else. There’s a conversation to be had about character archetypes, but for now, we will focus on the fact that stereotypes are far too limited and based in the same silly logic that negative stereotypes come from.

Representation also matters for minorities whether that is in race or gender. It is inspiring to many young individuals as well as those of the older generation to see themselves reflected in stories, be they movies or other mediums. To see someone who looks like you, who is a part of your culture, your heritage and your identity achieve big things, survive and carry on can be powerful. People like seeing people like them do well. (Nadal, 2021; Williams, 2023; YouPress, 2022)

Representation doesn’t just limit itself to appearance. Representation lies in action, whether it’s becoming a doctor, an actor, an engineer. It comes in writing your stories and expressing yourself to the world. It comes in simply existing and showing others that they can be more and that they can be happy doing it. Sometimes it can be something nice and simple, like seeing a piece of your culture represented in a medium. Other times it can be moving and, especially for many of the younger generations who might feel lost or without direction, it can be powerful. (Overton; American Psychological Association; Nasimi, 2023)

Seeing Ourselves on the Screen

Over the years, many Pacific Islanders have taken up the task of reviewing and correcting our history. On top of that, Pacific creators, writers and artists have been making the effort to portray our stories from our point of view (Hereniko, 2019). Writers like Albert Wendt, Lani Wendt Young, Epeli Hau’ofa, Taika Waititi and Kiana Davenport have written extensive works both about historical and contemporary polynesia as well as a litany of poems and artistic works (Goodreads, 2024; Academy of New Zealand Literature, 2024; Maddison, 2022).

Art forms have also evolved. Books and theatres are no longer the only form of entertainment. Movies, comics, graphic novels, short stories, video games and other forms have become major industries and with them, a new generation of creatives.

Polynesians have seen a lot of representation in the wrestling scene, with Samoan names like Fanene Leifi Pita Maivia (born Fanene Pita Anderson), Dwayne ‘the Rock’ Johnson (his grandson) and the Anoa’i family of whom wrestling legends like Roman Reigns, Solo Sakoa and the Usos were a part of. Alongside them was Tonga’s assortment of athletes, including Tonga ʻUliʻuli Fifita, Tama Tonga, Tagaloa and Hikuleo. (Desk, 2024; Tamatonga, 2024)

Just recently, Polynesian wrestlers have been at the forefront of the wrestling world. The Bloodline, a collection of primarily Samoan wrestlers, has recently been catapulted into wrestling fame, becoming headliners for the WWE and inspiring a new generation of pacific islanders.

From wrestling, none have achieved so great a career in the movies as Dwayne the Rock Johnson. The Rock has become a superstar in the industry and much like his fellow wrestlers, has become one of the faces of the Industry. Alongside them, Taika Waititi has emerged as one of the best filmmakers of the modern age, with films tackling both the issues in the Pacific and abroad.

One of Disney’s recent great successes was Moana, a film set predominantly in Polynesia featuring a cast of Polynesian characters, with a sequel set to come out. This landmark film was also one of the precious few times Polynesians were depicted with our trademark frizzy hair. Something as simple as the accurate depiction of our hair brought joy to a lot of people. This movie was released some years after Lilo and Stitch, another resounding success that celebrated many aspects of Hawaiian culture.

Another medium where Polynesians have seen a lot of representation has been, ironically, in the emerging art form of video games.

Apex Legends features a Polynesian character, Gibraltar alongside Mad Maggie, a Maori woman. Overwatch has also recently added Mauga (Mountain in Samoan), a playable character who subverts the jovial Polynesian archetype by hiding a degree of cunning behind the smile. Aside from him is Roadhog, another Maori character and one of the original characters on release. Additionally, many cosmetic items in the games were made inspired by Polynesian art. True, they’re all bigger than the other characters, but considering what we had before, ala some poor white folks who got spray tanned, it’s a dramatic improvement.

Speaking of Polynesian art, the proliferation of social media and online opportunities has allowed many independent Polynesians to find both success and appreciation online. Musicians, visual artists and storytellers have seen worldwide recognition alongside many other minority groups who now have the power to dictate how they were seen by the world. The potential for Polynesian art and artistic expression has only increased over the years.

Nothing’s Perfect

Despite all the progress, like many representations in media, there’s a level of nuance that needs to be respected. It is very easy to put a Polynesian individual in a movie and call it a day, but that’s not nearly enough, at least if you want to portray Pacific Island peoples accurately. Moana is not guilty of any unique mistake that hasn’t done before. Even with movies such as Mulan, Brave and Aladdin, Disney’s creative teams often blend cultures together (in Mulan, the setting is set in China, though in the beginning of the movie, Mulan wears Japanese makeup styles).

Disney is an entertainment company after all and doesn’t need to portray anything with incredible accuracy.

Mistakes however are worth nothing. One point of contention with Moana lies in its use of the Kakamora, which are evil spirits originating from the Solomons. This is important because no Solomon Islanders make an appearance in the film, yet a touchstone of their culture does. While many Polynesians were happy to see themselves represented, it would be remiss to represent the Pacific and not mention two of its three major groups. Melanesians and Micronesians are rarely ever acknowledged beyond the Pacific outside of academics.

Representation of one should not come at the cost of another. There are a variety of Polynesian folk myths that could’ve been used in place of the Kakamora, but the creators chose them instead. (Hawley, 2024)

This is not an indictment of the creators, but it is a matter of colourism that Melanesians and Micronesians are so rarely considered. Much of this comes as a result of colonial attitudes that have persisted to this day, with little merit. Moana however is not explicitly about the sailing techniques of Polynesia, so some liberties can afford to be taken.

Moana is not the only example of Polynesian representation. But it goes without saying that it has hit massive levels of popularity. It is beloved by many, but other Pacific Islanders have taken the time, in light of the sequel, to look upon the movie more critically. (Dittmer, 2021)

One of the more disliked changes was the look of Maui. Maui, in Polynesian culture, was a renowned trickster. Young, brash but cunning and prone to tricking his opponents with lies, akin to Loki but he was known as a ferocious warrior who beat the sun into submission, which sounds a lot like Thor. These are just reference points for any non-Pacific Islanders reading, but the idea is that Maui is intelligent, brave, strong and meant to be someone who is good at manipulating other gods or outsmarting them.

So his portrayal in Moana, that of a mighty warrior who hits things hard but isn’t that bright, was controversial. Again, refer to the stereotype. His appearance also caused a stir, as it relied on the good old big, strong Polynesian cliche who is also heavy. Now, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Overweight people tend to be cast as idiots or as something to be avoided, with very little in between. That is, if they even are represented. (Koranne, 2023; Konstantinovsky, 2023; National Library of Medicine, 2003; Rothblum, Solovay & Wann, 2009)

To Wrap Up

Thus far, you’ve listened to us prattle about how representation matters and how we need good representation. Because, in many ways, bad representation just falls back on tired storytelling beats and a lack of imagination.

Representation is valuable, both for the represented and those outside that group. Once people are represented, authentically, it is easier for others to empathise with them, to see themselves in them. Pacific islanders and our lower populations make us minorities in many ways. A long history of colonialism has affected the way the world sees us and how many of us see ourselves. Representation for islanders serves something much more than Pacific Islanders feeling good about themselves.

Representation breeds empathy. It allows us to see beyond the limits that can be imposed upon us and allows others to look upon us and feel kinship. These connections are going to be an invaluable part of our future. Especially in a world where the survival of our peoples, cultures and the very land we live on is in danger. Beyond that, it allows our stories to be told, and our stories to be remembered. Pacific Islanders, and indeed all people are more than the boxes they are forced into. The world ought to see them as such as well.